by Vic Attardo

Maybe you’ve never heard of George Toalson. That’s all right; he is is not exactly a household name. But I can assure you that millions of crappie — those fish we’re all crazy about catching — have heard of George. Also, those fish enjoy taking a big bite out of him. That’s because Mr. Toalson has created some of the most popular crappie baits on the market.

You’d have to be the CEO of a rival crappie lure-making company not to have some of Toalson’s creations in your tackle kit — and maybe even then you’d sneak in a few because everyone knows his baits are that effective.

Toalson creates lure shapes and colors for Bobby Garland – so you’ve heard of him or his baits.

“First, I make everything for myself, then I get them out to the public,” Toalson told me, as we fished the northern fishing factory of Pymatuning Reservoir in western Pennsylvania.

One of his “in progress” projects is to figure a way to manufacture weedguards into a tiny crappie jig. “There’s not much lead on a crappie jig, particularly a one-sixteenth ounce jig or smaller, so we’re trying to come up with the manufacturing process.”

His fall fishing tactics are great, but first here’s the story about one of the favorite, hot colors called Monkey Milk. Toalson fashioned the color itself but had no clue for a name. One day while in the Oklahoma Bobby Garland factory, Toalson, along with PR/advertising whiz, Gary Dollahon, were walking around with an example of the new color asking employees what it reminded them of. They were at a loss for catchy nomenclature until they came upon Diane Thorton. Thorton, at that time, had worked in the factory for thirty years, so had seen a lot of rainbows bloom and fade. Without skipping a beat, she said, “You know that looks like monkey milk.”

The advertising bells in Toalson’s head must have peeled loud and clear at that moment. Still, there was another question that had to be asked. “Well, Diane, have you seen monkey milk.?”

“No. But I think it would look like that.”

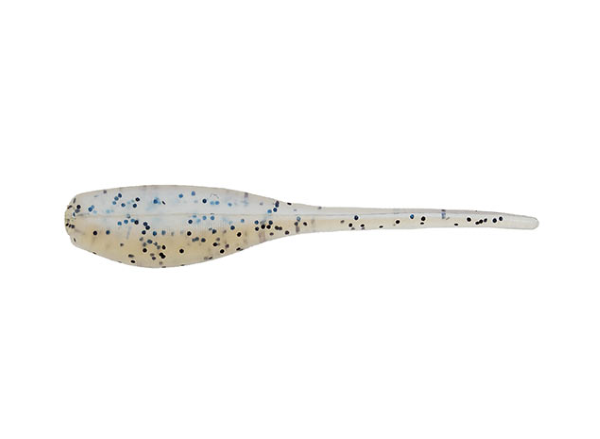

Monkey Milk is a creamish, opaque sort of thing laced with black dots, like dog ticks on a seeded dandelion head.

And so, one of the most famous color monikers, outside “firetiger” and “kudzu,” was christened. Though it’s just not an achievement you put on your tombstone.

The fact that Monkey Milk has become so popular, so darn effective, is a testament to Toalson’s imagination and perhaps bizarre jungle dreams.

From ‘Monkey Milk’ we now move to a story on cormorants — you know, every fisherman’s favorite bird — but this story is truly about fall crappie fishing.

It seems, according to Toalson, when the cormorants “come home to Oklahoma” after spending the summer up North where they’re as welcome as mosquitoes, the OK crappie change their pattern. A kind of multi-phasic disruption as when the swallows return, en masse, to Capistrano.

“Where the crappie were holding at 12 feet,” Toalson explains, “when the cormorants (who love to eat crappie) arrive they go deeper than twenty feet.”

Perhaps you’ve seen an immense flock of cormorant suddenly jump off their perches (I have in South Carolina) and start flapping their wings across the water, like a mad herd of whirling dervishes.

Herd is the operative word here because that’s exactly what the cormorant flock is doing — herding the crappie school into a limited space. They drive the crappie against a shallow shoreline, against rocks, even bridge abutments. Then they dive on the fish and the underwater flying cormorants have a feast. (Go find a U-tube video of a cormorant flying underwater, it will astound you.)

But as Nature giveth, she also take-it-away because cormorants are somewhat limited: they can’t dive more than 20 feet. They’re great at fly/swimming in the shallows, particularly in the three to 15 foot range, but they’re not exactly deep-diving crankbait cormorants.

Now it’s becoming clear, I hope, why Toalson says immense schools of crappie move into deep water in the fall. They’re trying to avoid the nasty fish-eating cormorants.

Little doubt then that his number one fall pattern is to fish deep water.

“I am not a spider rigger and I don’t use a color selector. I fish deep, the old fashion way, using a vertical jig. As for color, I use the one that I can see at the greatest depth.”

Guess what one of his favorite colors happens to be? It’s initials are M and M and it don’t melt in your mouth.

Toalson’s fall pattern is that tried-and-true method of working deep ledges, channels, brush piles etc. where deep crappie hang out. And he’s no wind sailor. “I want to stay on the same spot and shop till I drop,” he says whimsically.

In the not too distant past, when he found the deep-holding crappie, he would anchor over and around them. Of course, anchoring takes a lot of work, a lot of pull as it were. So these days, he has gone high-tech. Instead of roping an iron, he relies on the newish electric motors that hold a boat in place.

“I used to always anchor, now I use a spot lock (Minnkota Spot Lock).” he acknowledges, a wiry smile denoting less work and more fun appears on his face.

In Toalson’s manner of deep-water fall fishing excessive boat movement over a crappie school is a killer.

“For my kind of fishing, I don’t want to drift around. I don’t want to spook the school. I want to stay still and let my jig work for me.”

Now it’s important to understand that cormorants aren’t the only things that have chased crappie underwater. As many great fishermen have done, they’ve seen their quarry from the quarry’s viewpoint.

Like those other greats, Toalson has scuba dived on the crappie, and this hard work has paid dividends. “I know how they are positioned down there,” he says.

When it comes to brush piles and sunken trees and the lot, crappie have a definite swimatude, Toalson explains. “They lay under the limbs. They don’t lay on top of them.” He says that though he is positioned over, or nearly over, his desired crappie hotspot, “I cast to them more than fish straight down. If you can feel that limb, then you let it fall back over, that’s when you’ll get your bite.”

Now I bet you can understand why Toalson is so interested in manufacturing a crappie jig with a weed guard.

Nine of ten crappie anglers, when desiring to drop a jig so that it plumbs underneath limbs and such, will search through their tackle boxes for heavier jigs. But not Toalson. He’ll use a jig as “itty bitty” as a 1/48 ounce with a size 8 hook. His rod is a 6 foot G. Loomis ultra light.

“Don’t use a heavier jig; use a split shot,” he cautions. “The split shot won’t get hung up like a heavier jig.”

He places the shot between 12 and 18 inches above the Itty Bit jig.

And there is one other thing that insists on for real crappie success. “Use a loop knot when tying on the jig. Don’t ever tie a tight knot. A loop knot allows the jig to swing free.”

So now it all comes together. What Toalson does in the fall is, one, watch for the cormorants to return; two, fish the deeper water where the birds can’t go; three, cast tiny jigs and use split shot for a vertical presentation and, four, among a few others, use the color Diane Thorton named without even knowing what monkey mild was. Way to go Diane. You’ve helped Toalson and many others catch crappie.